This was meant to be a book review. But it got bigger.

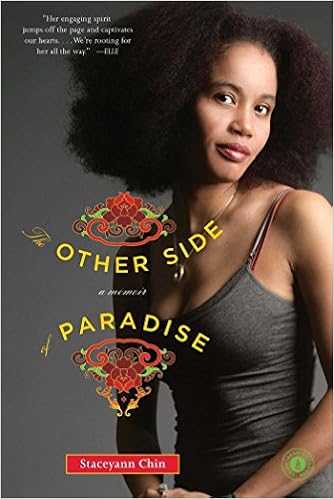

Book: The Other Side of Paradise

Author: Staceyann Chin

Genre: Memoir

Staceyann Chin writes her memoir with painful honesty. The Other Side of Paradise sometimes trips over uneven dialogue and wobbles with a mostly unreliable narrator (how accurately do any of us remember our youth?) but the story it carries is all too familiar.

Recounting her early childhood and adolescence in Montego Bay, Jamaica, Chin takes us slowly and deliberately through her memories of growing up with her grandmother (a quintessentially Jamaican way to be raised), and receiving instruction on how to move through the world as a girl-child in possession of that most sacred body part – the “cocobread”. This is standard socialization for Jamaican girls. The minute we are born and our gender declared, we receive ear piercings, skirts (with tights) and endless repeated admonishments to ‘keep yuh legs close’ and ‘don’t mek nobody touch yu dere’.

Unfortunately, as Chin discovers in her prepubescent years, there are too many people (usually men) who want us to do the opposite. Who, as soon as backs are turned and doors are closed, are only too eager to “get the first sample” and “pick mi fruit when it ripe”. I call her memoir painfully honest because by revealing the unpleasant reality of her life in Jamaica, Chin has catapulted the familiar trauma of black girlhood into the bright lights of the world stage. And it’s not a flattering sight.

My reaction to the book is necessarily tangled in years of social conditioning and the normalization of trauma. I read Chin’s recitation of events with a matter-of-fact outlook, empathizing with her sexual assaults but consoling myself (rather emptily) that she is lucky to have escaped with relatively little harm.

On the other hand, accustomed as I am to books where the protection of white girls is paramount (and the slightest brush of a hand invites Child Protection Services), I’m acutely aware that this mistreatment of young girls’ bodies is not normal. When I read Staceyann Chin’s memoir through the eyes of an international audience that I imagine to be privileged and protected, alarm and outrage butt heads with my pragmatic resignation.

It’s also more than a little embarrassing to think about first world country citizens reading her book and finding out that this is actually how children are treated in Jamaica.

Despite great personal struggles against the fabric of a society that would have loved nothing more than to strangle her voice, Chin made her own happy ending – emigrating to New York and becoming a poet and activist (and now, a mother).

I loved the representation in this book – it’s honestly the first time I’ve ever felt ‘seen’ in any kind of literature. The depictions of Montego Bay and its surrounding communities, the classism inherent in Jamaican society, the racial tensions that simmer just below the surface, the burgeoning sexuality of an adolescent girl in a country where female sexual expression is anathema – everything resonated with my life up to this point. I am grateful to Staceyann Chin for putting this uncomfortable, familiar, strangely hopeful book into the world, and I can’t wait for her next.

Book: Queenie

Author: Candice Carty-Williams

Genre: Fiction

I did not like this book when I first read it. Not one bit. I thought Queenie was irresponsible and needy, I thought the descriptions of her Jamaican grandparents came across as condescending, and the vividly described sex scenes were more than a little gratuitous. The narrative tense kept switching between past and present, sometimes in the same paragraph (this might just be my electronic copy) which is a huge pet peeve of mine. Not to mention the gallons of infuriatingly casual racism that went totally unchallenged until the third act. Nothing about this book recommended itself to be read a second time.

That being said, I think Queenie should be required reading for every second generation immigrant black girl struggling to straddle two cultures and losing her footing in both.

Through her eponymous main character, Candice Carty-Williams pulls us along for a treacherous ride through a year in the life of a woman on the brink of self-destruction. While hinting clumsily(/skillfully?) at the ruins of a traumatic past, the events that have shaped Queenie into the shell of a woman she is today aren’t fully revealed until the last few chapters. This is a deft delivery that evokes less shock value and more cathartic release, which at the end of the book is really what we’re hoping Queenie can achieve.

Most of my grievances with Queenie are easily smothered when she finally accepts that she has a problem. In mental health examinations, we call that insight: a person’s ability to acknowledge that they are, in fact, not well. Carty-Williams should be applauded for her realistic portrayal of the therapeutic process because no one magically gets better once they identify the source of their trauma; the work gets lighter, but usually not easier.

I give Carty-Williams another nod for her determined activism. Overtly, Queenie tries repeatedly to convince her editor to let her write serious pieces about the Black Lives Matter movement, but more subtly Carty-Williams uses sleight of hand to declare her stance on boundaries around black women’s hair, body positivity and the fetishizing of black bodies.

As for my reactions, for the second time in a fortnight I am left reeling from warring emotions. When Queenie finally divulges the incidents of her past, including abuse by her stepfather, my reflex thought is “Thank God it was just verbal/emotional abuse, that’s not so bad”. But when her therapist is appalled by the revelation I realize I too am a victim of generational trauma bleeding into our culture.

Heal.

So we don’t have

carla moore

another

generation of

trauma passing

itself off as

culture.

The collective Jamaican perspective on the care and wellbeing of children is completely fucked. And we have yet to accept that there is a problem.

The local news reported on two separate cases involving the assault of underage girls by police officers. In one case, the girl-child was in police custody, removed from an unstable home situation for care and protection. Care. And. Protection.

Weekly, almost daily in Jamaica, there is another story of a child being raped, murdered; a woman being assaulted, killed. The onslaught of reports on violence, graphic headlines and news segments that are way too detailed raises feelings of helplessness, anger and apathy. We become preoccupied with trauma (“have you heard/seen the latest story of another broken black body”), we withdraw, we increase our vigilance.

We are traumatized, vicariously, from witnessing the trauma endured by a person who looks like us, who inhabits our skin. The repeated pummeling of women’s bodies, girls’ bodies splays open the widely-held notion that girls and women are little more than chattel, our bodies commodities to be used and ultimately discarded.

Black women from birth have historically been branded and boxed. We’ve been slapped with labels like angry, aggressive, slutty, bitchy. We’ve been forced into rigid expectations for body type, fertility level and faithfulness, and when social sanctions fail to “keep us in line”, we’re dragged back into bounds by peer-approved physical violence.

It has to stop.

Black and brown children are supposed to feel safe and enjoy their childhood. That can’t happen if eleven year old girls keep reading newspaper articles about eleven year old girls being kidnapped and murdered. Children should be nurtured and protected and allowed to flourish in their own time. That can’t happen if we keep using their bodies as excuse and punishment. Chin and Carty-Williams have given us books that reflect the fractured and failing state of our society.

When we look in the mirror, what looks back?